The Bel Canto Tenor’s Voce faringea

secret of their brilliant and flexible high notes

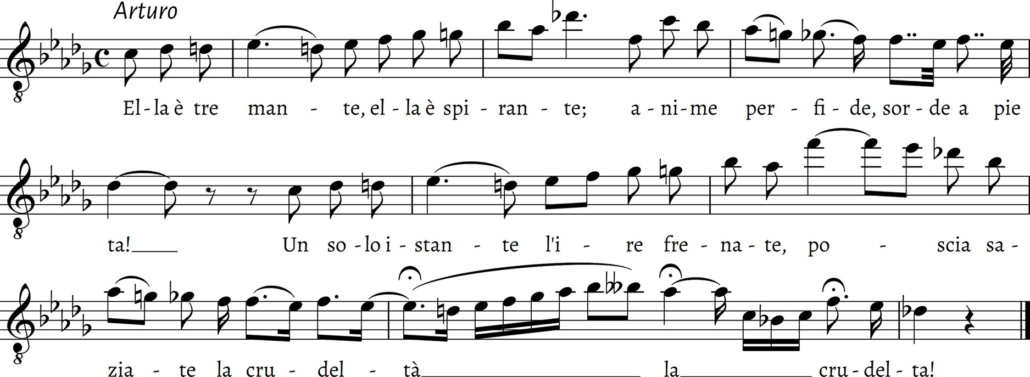

Many tenor roles in the operas of the primo ottocento have an exceptionally high tessitura—often with notes well above C5 or D5. The best-known example is probably Arturo’s arioso “Credeasi misera” from Bellini’s I Puritani, which is composed up to F5. Normally, such high passages are beyond the vocal compass of modern tenors; thus, roles like these not only raise the question of how tenors in the early 19th century would have coped with such tessitura and extreme high notes, but also raise questions regarding historically informed performance practice, the aesthetics of Western classical music, and how singers today should perform such roles in an effective and vocally healthy way.

The book Voce faringea: Eine Kunst der Belcanto-Tenöre. Geschichte – Physiologie und Akustik – Übungen by Alexander Mayr has been published (November 2018) by Bärenreiter.

More details and order (website of Bärenreiter)

The so-called voce faringea offers an answer to these questions. Essentially, it is a forgotten historical singing practice used to extend the upper range of the voice; here, the falsetto, typically heard as a weak or feminine sound, is modified by the singer into a vocal quality that is more tenoral and powerful. During the period of its employment, the resulting sound was considered homogenous with that of the lower registers and no longer perceived as a falsetto vocal color. In an exemplary fashion, this register mechanism mirrors a preromantic vocal ideal of sound that seems clearly divergent from ones prevalent today.

Eighteenth and 19th century vocal pedagogical literature employed various, confusing, and even contradictory terminology for the different voice registers; however, most pedagogues were in agreement regarding the particular aesthetic merits of each register—mainly, chest and falsetto. In addition to these two registers, some vocal treatises of the era make mention of a third register mechanism tenors could employ to particular artistic advantage. It was often described as an intermediate register or a special mechanism connecting the falsetto and the chest register, and was perceived as a mixture of the two, often called voix mixte (mixed voice). Vocal maestri and physiologists used different terms to denote this vocal mechanism, including head voice, falsetto or fausset/faucet, voce mezzo-falso or middle-falsetto, Schlundkopfregister, feigned voice, voix sur-laryngienne, and voix pharyngienne (pharyngeal voice or voce faringea).

The term pharyngeal voice was coined by Herbert-Caesari and was first used to describe this particular vocal mechanism in his 1950 article “The Pharyngeal Voice,” in The Musical Times, and further in a chapter from his book The Voice of the Mind (1951). Herbert-Caesari explains that the term pharyngeal voice is translated from the Italian voce faringea, and was used by exponents of the “old school” solely to describe a peculiar tonal quality produced by a distinctive mechanism. He adds that the tenors of the Rossini/Bellini/Donizetti period were taught to sing with voce faringea—very carefully mixed with both the falsetto and the chest registers—and furthermore, that this method enabled (particularly) tenors to sing their highest notes with ease and brilliance.

In accordance with formerly prevalent vocal ideals, at least according to historical written sources, these tenori di grazia did not produce their voices with dramatic force but rather with elegance and suppleness up through their highest range. And yet the special vocal technique they employed to produce high notes considerably beyond C5 with absolute security and facility—as well as gradations between pianissimo and fortissimo throughout their entire range—gradually fell into obscurity.

Excerpt from Arturo’s arioso Credeasi misera from the third act of Vincenzo Bellini’s I Puritani.

With the tenor, we come across yet another register (…) For many tenors, the “mixed vocal quality” cannot be attained even through the most diligent studies, whereby for some natural talents it appears to be inborn. The tenors who possess this sing often to B-flat, B, even to C with the greatest ease and without considerable strength, and their sound has so little falsetto quality that this leads to the false opinion that one or the other great tenor has sung to high B or C in chest voice!”

(Sieber, Ferdinand (1851). Das ABC der Gesangskunst. Ein Kurzer Leitfaden beim Studium des Gesanges von Ferdinand Sieber in Dresden, S. 118 f. )

(…) balancing between registers, the singer gains a beautiful, marrowish, mixed tone, seeming to retain the strength of chest voice and yet protect the voice as in falsetto, without the feminine sound of falsetto.”

(Schmidt, Friedrich (1854). Große Gesangschule für Deutschland. München: Selbstverlag, S. 180)

During the second half of the 19th century, the vocal tradition of these great tenors ultimately went out of fashion, and a new, more dramatic verismo vocal ideal took hold. Musicological scholarship attributes Gilbert Louis Duprez’ interpretation of Arnold in Rossini’s Guillaume Tell, first in an 1831 performance in Luca, Italy, but more significantly in the 1837 Paris revival, as being a primary catalyst for this development. Duprez’ high C5 (ut de poitrine) was not sung in the traditional bel canto falsettodominant vocal mechanism, as the famous tenori di grazia Adolphe Nourrit, John Braham, or Giovanni Battista Rubini had sung it, but rather in modal (chest) register, similar to contemporary tenors. Duprez’ ut de poitrine became the turning point after which the vocal ideal of the bel canto tenors, and subsequently the technique for developing voce faringea, were lost. The term voce faringea has been chosen over other terms to avoid confusion and unwarranted associations with the modern falsetto voice, as well as misconceptions surrounding various other terms.

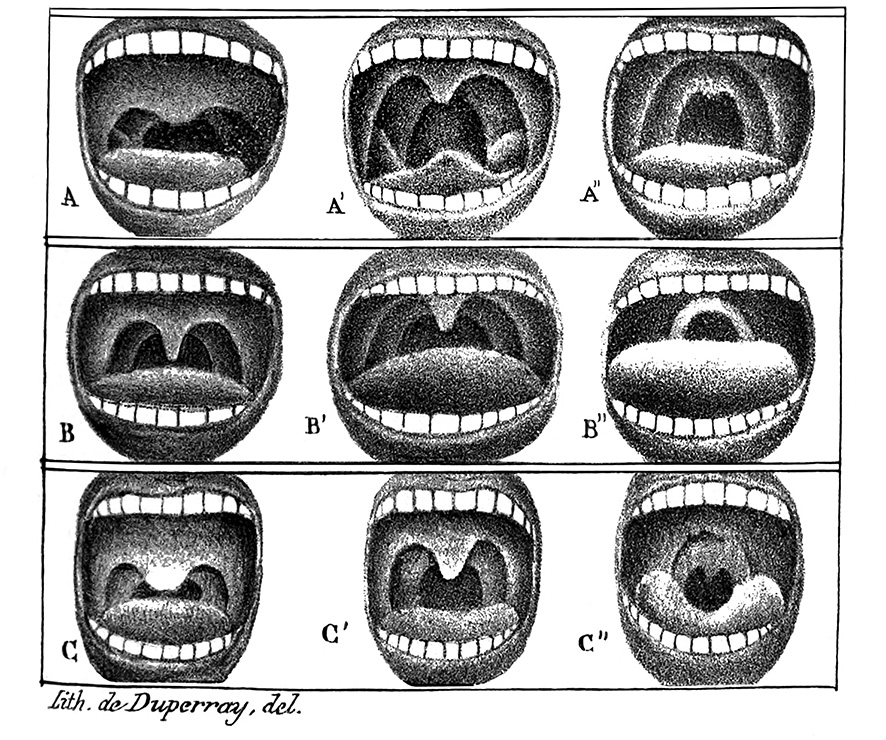

Observations made by vocal pedagogues, medical doctors, an physiologists, documented in several vocal treatises as well as physiological and anatomical writings from the early 19th century, are particularly revealing with regard to training different vocal registers in the corresponding operatic tradition. Accordingly, many authors have mentioned the importance of specific muscular adjustments in both the vocal tract and the larynx for producing the “mixed” voice. Bennati, an ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialist at the Paris Opera and trained singer, could study the physiological differences between vocal registers on himself and the best singers of the time. Both a contraction of the pharynx by lateral approximation of the pharyngeal walls in the area of the isthmus faucium and a narrowing of the aryepiglottic space were identified by him and other maestri and physiologists of that time as a requirement for the production of the mixed register.

Lepelletier de la Sarthe illustrated this constriction of the pharyngeal space in voix pharyngienne (the French term for voce faringea) also observed by Bennati. But in addition, an increase of vocal folds mass by slightly altering the coordinative contraction of the thyroarytenoid (TA) and cricothyroid (CT) muscles and a strengthening of glottal adduction were mentioned as physiological basis for developing a falsetto tone into the mixed voice.

The mouth cavity (A: soprano at rest, A’: in chest voice, A”: in head voice. B: tenor at rest, B’: in chest voice. B”: in voix pharyingienne. C: baritone at rest, C’: in chest voice, C”: in voix pharyingienne. Table made from studies by Francesco Bennati. (Lepelletier de la Sarthe, 1833, appendix)

The aim of my artistic research has been the artistic and scientific reconstruction of this long-forgotten type of singing, known at that time as voce faringea. The artistically aesthetic work was based on an interdisciplinary combination of artistic (experimental) practice with musicological, acoustic and physiological research. The voice served thereby equally as a mediator between the disciplines as well as the object of research, tool of experimentation and objectifying instrument. Finally, I was able to present and document my research findings both scientifically in the context of physiological-acoustic studies and artistically with my interpretation of the extremely high tenor role of Arkenholz in Aribert Reimann’s opera The Ghost Sonata at the Frankfurt Opera in January 2014.

My central goal has been to rediscover these specific qualities of vocal sound, as well as to open new perspectives on historical performance practice in vocal literature of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Presentation – voice diagnostics course of the ÖGLPP, Vienna 2015